14.2. Supernova¶

A typical time scale for core collapse of a core collapse supernova is 0.5 second, which is exceptionally quick. Followed by a bounce, a supernova could be successful.

The energy released in a supernova is typically \(\sim 10^{51}\mathrm{erg}\sim 6.24\times 10^{56}\mathrm{MeV}\), which is usually dubbed as \(1\mathrm{B}\) or 1 Bethe. John Cherry Jr wrote in his thesis that this is the energy to unbind a 10 solar mass star gravitationally. Blowing away most part of the stars is what exactly a supernova does.

Another astonishing fact about core collapse supernova is that almost all (99%) of the gravitational binding energy will be transfered to neutrinos.

Features of Type II supernova from observation in astronomy are listed below [Budge].

They have asymmetic remnants,

The elements are not uniformly distributed in the remanants,

Neutron stars obtained high velocities from somewhere,

…

We are most interested in neutrinos. From the view of observations, our detectors in the solar system can detect neutrino flux with energy spectrum and time evolution.

14.2.1. Supernova Explosion¶

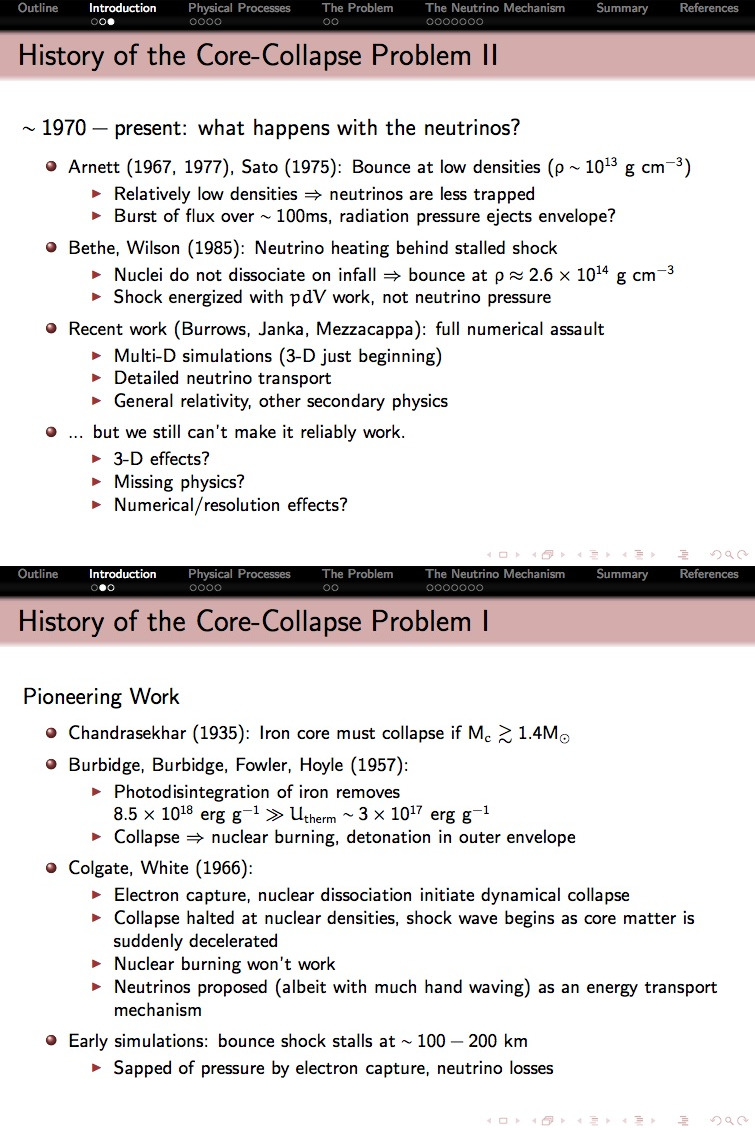

For a short review, Timothy Brandt’s slides are perfect for this purpose.

Fig. 14.14 From Timothy Brandt.¶

14.2.1.1. Bounce to Explode¶

The first idea about core collapse supernova model is to facilitated the idea of bounce on the surface of proto-neutron star.

It should be notice that heat capacity is negative for a star balanced by nuclear fusion until other short range repulsive forces is comparable with grativational force.

Thus we expect a violent destiny in the end of some stars when the fusion is not suffient to fight the gravitational force leading to a runaway process. The star collapses.

However, collapse of the star is usually countered by other forces such as nuclear strong forces. When the core reaches nuclear density which is the limit of compression of nuclear materials, a bounce occurs.

But

However, the bounce alone is not enough. The shock of the explosion will stall and fall back onto the proto-neutron star. More energy should be deposited into the shock in order to revive it. Hence neutrino heating is introduced.

Numerical simulations show that simple models of neutrino heating is still not sufficient. To revive the shock, we have to develop more models.

Is the energy density in the shock more distributed or concentrated in small regions? This is related to convection and the angular distribution of neutrinos.

Do we have more electron flavor neutrinos at the shock? Electron flavor neutrinos are the primary source of neutrino energy deposition into the shock. This is related to the neutrino flavor conversion.

Numerically, neutrino transport in supernova is very hard if flavor oscillations are considered. One of the trick is to estimate the flavor conversion at different distances then implement it as a flavor profile in the simulation.

So we need some energy input to the materials. Then we remember the toy problem named astro blaster. We could assume the bounce happens but leaves some materials back at the star while thowring part of materials out of the gravity well.

Or we simply need energy input to the shock. One of the sources is radiation pressure which is always there. Another one is nuclear reactions.

Well, there is another reason that a simple bounce won’t work. It is the ram pressure. As the shock moves through furthure out, it experiences the friction of the surronding materials, or the ram pressure, \(p_{ram}\sim \rho v^2\), which could be large. Assuming the post chock pressure is \(p_{ps}\), \(p_{ps}<p_{ram}\) will kill the out-going shock.

Towards a successful explosion

Timothy Brandt mention in one of his talk that

We need to either increase \(p_{post−shock}\), decrease \(p_{ram}\), or both, by:

Depositing additional energy behind the shock,

Changing the nuclear equation of state (nope: e.g. Burrows & Lattimer 1985),

Using radiation pressure (nope: \(L_{typ}\sim 10^{53} \mathrm{erg s^{−1}} \ll L_{Edd} \sim 10^{55} \mathrm{erg s^{−1}}\)) or

Using progenitor models with steeper density profiles.

So we pretty much rely on more energy deposition to the shock.

We could use

more nuclear burning,

\(\nu_e + \bar\nu_e \to e^+ + e^-\) then the annihilation of them,

the neutrino mechanism which is a delayed neutrino heating.

14.2.1.2. Neutrino Mechanism - Delayed Heating¶

Supernova neutrinos are typically within a range 5-40 MeV. Usually neutrino interactions with matter is negligible. In the environment of supernova explosion, the mean free path for neutrinos is of the order

Neutrino can heat up the materials through neutrino and antineutrino capture processes. Meanwhile, we have neutrino cooling through URCA processes.

Neutrino Cooling

URCA processes:

Electron capture: \(p+e^-\to \nu_e + n\),

Position capture: \(n+e^+ \to \bar\nu_e + p\).

Cooling is at a rate that is proportional to \(T^6\), which is fast.

There exists a region of net neutrino heating. To doposite sufficient energy, the matter within this region has to stay long enough to recieve as much as the energy that neutrino can deliver.

Multi-dimensional simulations seems to increase \(\tau_{res}\) (the time of stay for matter within the heating region). And more matter can move through the region of heating which allows more heat to be gainded and transfered.

14.2.1.3. Convection¶

Convention in the core can speed up the neutrino escaping, which can increase the power of neutrino heating.

But [Dessart2006] showed that the core has motions along cylinders due to rotations and it prevents large convection.

14.2.1.4. General Relativity¶

References

See Timothy Brandt.

General relativity effect tends to compactify the core thus producing more energetic neutrinos.

However, neutrinos lose kinetic energy as it climb out of the gravitational well.

Probably a higher order effect.

14.2.1.5. Other Ideas¶

Adam Burrows et al developed a mechanism that allows protoneutron star to vibrate and explode the star [Burrows2006]. In their model, neutrino energy deposition is not necessary.

14.2.1.6. Efforts¶

Budge mentioned that several directions are being explored for more successful supernova models. [Budge]

Hydrodynamics,

Boltzmann transport,

General relativity corrections,

Neutrino physics.

14.2.2. Boltzmann Transport¶

14.2.3. Neutrino Oscillations¶

In a supernova explosion, many effects come into neutrino oscillations.

Vacuum oscillations;

Matter effect:

MSW;

Neutrino self-interaction:

spectral swap;

spectral split;

14.2.4. Refs & Notes¶

- Budge(1,2)

Supernova Theory: Simulation and Neutrino Fluxes by Kent G. Budge

- Burrows2006

Burrows, A., Livne, E., Dessart, L., Ott, C. D., & Murphy, J. (2006). A New Mechanism for Core‐Collapse Supernova Explosions. The Astrophysical Journal, 640(2), 878–890.

- Dessart2006

Dessart, L., Burrows, A., Ott, C. D., Livne, E., Yoon, S. ‐Y., & Langer, N. (2006). Multidimensional Simulations of the Accretion‐induced Collapse of White Dwarfs to Neutron Stars. The Astrophysical Journal, 644(2), 1063–1084.