16.2.1. Cosmic Neutrino Background¶

In big bang cosmology, neutrinos became independent when the expansion rate which is characterized by \(\Gamma_H=G_N (kT)^2\) exceeds the rate of weak interaction \(\Gamma_W=G_F (kT)^5\).

Rates

The weak interaction cross section is approximately \(\sigma\sim G_F^2 (kT)^2\) and neutrino density drops according to \(n_\nu \sim (kT)^3\). As we can imagine, the weak interaction time scale for neutrinos is given by \(t_\nu \sim \frac{1}{n_\nu \sigma} \sim \frac{1}{G_F^2(kT)^5}\). 1

The neutrinos decouple when we have the rates comparable, which is

We find the energy scale is MeV while time scale is second. Also notice the decoupling for different flavors should be different.

As a result of expansion, those cosmic background neutrinos should be very cold.

Number density: 112 neutrinos per cc for each flavor. This 112 includes both neutrinos and antineutrinos.

Temperature: 1.94K which corresponds to \(1.67\times 10^{-4}\mathrm{eV}\).

de Broglie wavelength: \(\lambda_\nu = \frac{h}{p_v}\sim 2.4 \mathrm{mm}\) when we assume that \(p_v\sim 3T_\nu\).

16.2.1.1. Interactions¶

Those neutrinos are not really relativistic. Thus we should be careful when dealing with the interactions.

All we need to do is to calculate the scattering and use the fact that refractive index is given by 1

where \(M(0)\) is the forward scattering amplitude.

As an example, the refractive index for \(\nu_e\) and \(\bar\nu_e\) are given by 5

where \(\pm\) is for neutrino and antineutrino respectively, \(N\) is for target number density, \(Z\) is the charge (atomic number) of target and \(A\) is the mass, \(E_\nu\) is the neutrino energy. 5 I have an exrtra \(2\pi\).

Here is a table of the refractive index for all neutrinos on matter for nonrelativistic neutrinos where I used \(T_\nu\) as the kinetic energy of neutrinos.

Flavor |

Refractive Index n |

Comment |

\(\nu_e\) |

\(1+\frac{G_F N (3Z-A)}{2\sqrt{2}T_\nu}\) |

|

\(\bar\nu_e\) |

\(1-\frac{G_F N (3Z-A)}{2\sqrt{2}T_\nu}\) |

|

\(\nu_\mu\) and \(\nu_\tau\) |

\(1+\frac{G_F N (Z-A)}{2\sqrt{2}T_\nu}\) |

No charged current |

\(\bar\nu_\mu\) and \(\bar\nu_\tau\) |

\(1-\frac{G_F N (Z-A)}{2\sqrt{2}T_\nu}\) |

No charged current |

16.2.1.2. Detection¶

Since the Earth is moving in the CNB, it has been suggested that we detect the dipole moment of CNB. Neutrinos ahead of the moving velocity will go cross an object on the Earth then generate a tiny force on the object. We might try to detect the force and compare it with the theoretical prediction, even though it is very hard.

Direct detection experiments using this principle have been proposed to detect CNB 2 3 4. However these proposals are without the reach of current technology. 1

How Hard to Detect

The number density of CNB neutrinos is about \(10^2\mathrm{cm}^{-3}\), which is comparable to the number density of CMB photons. CMB photons are so hard to detect, even though it is electromagnetic interaction. Now we are talking about weak interaction.

16.2.1.3. Resonant Absorption of Cosmic-Ray¶

This method was proposed by T. Weiler 6 . This section works as the note of his paper.

The basic idea is to look at the \(\nu \bar\nu\) annihilation on the Z resonance.

Background

Estimation of neutrino chemical potential is done using the limit that neutrino energy density should be less than the total energy density of the universe.

To calculate the energy density of the neutrinos we need the phase space density which requires the distribution. In this paper, Weiler used the Fermi-Dirac distribution assuming \(m\ll T\). (The reason is that we are looking at a distribution generated at early universe. This approximation is explained in J. Bernstein and G. Feinberg, Phys. Lett. 101B, 39 (1981).)

where \(\nu_i\) as the subscript means the flavor of the neutrinos, \(T_d\) is the temperature at decoupling of neutrinos, \(\bar\mu_i\) is the chemical potential, antineutrinos have chemical potential \(-\bar\nu_i\).

The next step is to implement cosmic expansion into this distribution. Comsic expansion will affect the momentum of the neutrinos,

where \(a\) is the scale factor and subscript \({}_d\) means the value at decoupling.

Define a new quantity \(\beta = \frac{a}{a_d}\), we can rewrite the distribution at any moment,

Using this distribution we can calculate the number density of neutrinos as well as the energy density of neutrinos or any statistical quantities,

Cosmic background neutrinos are nonrelativistic. To see this we need to compare the temperature of neutrinos and their mass. The masses are less than 1eV while the temperature from estimation using scale factor is actually \(1/\beta = \frac{T_{\gamma_0}}{2.7K}\times 1.66\times 10^{-4} \mathrm{eV}\), which is much smaller than eV scale. 6

A Simple Estimation of Neutrino Mass Constraint

Using the fact that neutrino energy density should be less than the total energy density of the universe, we could have a very simple upper limit constraint for neutrino mass. 6

As we have seen the neutrino energy density can be written as a function of chemical potential \(\bar\mu_i\) and mass \(m_i\). To do the esitmation, we set chemical potential to 0 and use degenerate neutrino gas,

where we considered the antineutrinos which brings the factor 2.

We also have

which differs from the modern results but the order of magnitude is correct. This is a good estimation.

Distribution and Temperature

One thing to notice is that temperature works similar as scale factor. The way to map temperature is to use the temperature of radiation. Temperature of radiation is given by 6

where \(\eta = \left( \frac{11}{4} \right)^{1/3}\), from which we can solve out the factor \(\beta\),

Put in the numbers, we have \(\beta = \frac{2.7K}{T_{\gamma_0}} 6.25\times 10^{3} eV^{-1}\).

Now we have a distribution that is related to the temperature of radiation.

Mean-Free-Path

As an estimation, the mean-free-path is given by

where \(n\) is the number density of background particles and \(\sigma\) is the cross section of the interaction.

The mean-free-path of cosmic ray among CNB is related to the cross section of weak interaction \(\sigma_W\) which in turn is related to the mass of the weak interaction boson \(M_W\) ,

In center of mass frame, \(s\) is calculated to be \(E\left\langle \epsilon \right\rangle\), where \(E\) is the energy of the cosmic ray and \(\left\langle \epsilon \right\rangle\) is the average energy of CNB. Notice that \(n_{\nu} \left\langle \epsilon \right\rangle = \rho_{\nu}\) where \(\rho_{\nu}\) is the energy density of CNB 6 ,

in which we use the fact that \(\rho_{\nu} < \rho_0\).

Can we find signature of CNB in cosmic rays? One way to think about this question, as stated in Weiler’s paper, is to think about what is the requirement for us to detect the scattering of cosmic rays by CNB. The most general constraint is that the mean-free-path should be smaller than the Hubble radius, otherwise the effect would have a scale larger than the Hubble radius which can not be detected now.

To apply this constraint, Weiler found that

But we do not see cosmic rays from far away at such energies because the universe is opaque to such particles, unless we have much higher density of CNB. In fact Weiler shows that we need at least \(10^4\) times of the current number density to see the effect.

Why Opaque

For electrons, inverse Compton scattering with electromagnetic background in the unvierse is efficient enough to decrease the energy of them. 6

Photomeson production is responsible for the elimination of protons.

Due to the magnetic field of the galaxies, stars, or even planets, charged cosmic rays will produce synchrotron radiation and lose energy.

Resonant absorption of cosmic ray lepton by CNB can produce a effect in opacity. 6

Resonant Absorption

Suppose the background particle is not in a certain energy state but rather in a distribution of states, the scattering integration would be different. In a simple case as Breit-Wigner form, the cross section is related to the resoant width of the background particles.

Using Breit-Wigner form, 6

where \(S\) is the spin average factor, i.e., the number of outgoing spin states divided by the number of incoming spin states, \(R\to l\nu\) means this is about a process for a resonant state to leptons and neutrinos, \(\Gamma\) represents the width of the resonant states.

Weiler shows in his paper that

More Explainations

More here.

\(W^{\pm}\) and \(Z\) are the candidates for such resonant states.

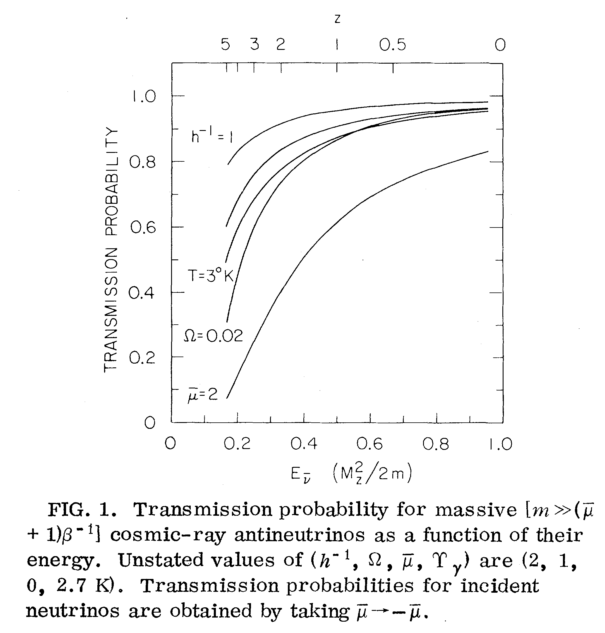

Then we calculate the opacity and the transmission probability of cosmic rays for different energys.

Suppose we have a source of antineutrinos at redshift \(z\), the antineutrino energy we recieved is \(E\), then the source energy must be \(E(z+1)\). The resonant scattering, should, if any, happen between the energy range \(E\sim E(z+1)\).

Fig. 16.1 From Weiler paper. The bottom horizontal axis is the recieved energy of the antineutrinos, the vertical axis is the transmission probability. The energy is in units of \(M_Z^2/2m\) where \(M_Z\) is the mass of the Z boson and \(m\) is the mass of neutrinos. The top horizontal axis is the nearest possible source of antineutrinos. If we detect antineutrino energy just at the resonance, the nearest possible source for such a resonant scattering is just in front of us.¶

16.2.1.4. Spectulations on Detection of the “Neutrino Sea”¶

Stodolsky wrote a paper back in 1974 where he investigated several ideas of detecting CNB.

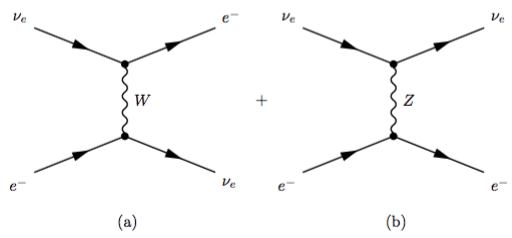

The interaction between neutrinos and electrons is spin dependent. Different spin states experience different interaction. This feature could possibly be used to detect CNB.

Fig. 16.2 Neutrino electron interaction. The left is charged current while the right is neutral current.¶

The Lagrangian for such interactions is

Red term is for charged current which exchanges the charge and blue term is for neutral current processes.

Fierz Transformation

In the context of weak interaction, for a Lagrangian,

exchange the field \(\Psi_2\) and \(\Psi_4\) doesn’t change the result.

The Lagrangian is called V-A theory because people define

The questionis how big the difference between neutral current only processes (such as muon or tau neutrinos and electrons interactions), and charged current plus neutral current processees (such as electron neutrino and electron interactions). To see this, we can apply Fierz transformation to the Lagrangian,

As we can see the difference is not so big. We can do estimations for electron neutrino and electron interaction only which is also a good approximation for other interactions.

To calculate the spin dependent energy, we should first estimate the current density of CNB neutrinos,

where \(v\) is the velocity of electrons with respect to the CNB.

Using this current density, we calculate the energy related to the two different helicity states of electrons,

The interaction energies for two different helicity states are,

which is similar to magnetic monent and B field interaction.

The next question, down this derivation, is the number density of CNB neutrinos \(\rho\), which is estimated as

Thus the energy split due to different helicity is

The Fermi momentum is gained from

Beta decay: \(p_F\leq 60 eV\);

Cosmological: \(p_F\leq 0.75\times 10^{-2} eV\),

which leads to

Is this small? Can we detect it? There are three different ideas given by Stodolsky,

electrons with mixed helicity states which develop different phases due to propagation,

ferromagnetic material of 1 ton has \(10^{27}\) polarized spins which can experience a torque,

He3 mixed to low temperature He4 can retain spin polarization for a long time which can be used to detect the phase difference.

The idea behind electron as detector is

electron Beams with equally \(\pm\) helicity states,

and - states have different energies = two different frequencies,

phase difference between the two states to be detected.

The phase difference is calculated as

which is roughly \(\left( \frac{p_F}{eV} \right)^3 rad\) for a light year travel.

This means we need to build very rapid electrons and maintain the spin polarization for a long time or we can use the fact that the Earth is moving with a velocity of \(250 km/s\) around the center of the galaxy. For the second choice we need to build a box of electrons which can retain the spin for a long time. Since the estimation also works for neutral current, the idea of He3 comes in.

The second method is to use a big chunk of ferromagnetic material, which contains a lot of palorized electrons thus is going to experience a torque due to the CNB.

The torque for 1 ton ferromagnetic material is

which is such small. Besides, we need to consider external magnetic field since this is a big block of ferromagnetic material. The author did propose to devise a method to measure this small torque using gravitational wave detectors, in our current view, LIGO.

16.2.1.5. A Possible Application of LIGO¶

Speed with respect to the CMB

The earth is moving through the CMB background at a speed of \(583,333\mathrm{m/s}\).

In the paper by Vogel 1, the force by these CNB on a sphere of radius

For an approximation, I use \(\nu_{relative}=10^{-3}c\), a proper set up of the experiment would be about the order of \(a_t\sim 10^{-38}\mathrm{cm/s^2}\).

A simple back-of-the-envelope estimation by assuming an constant acceleceration due to the CNB on the mirrors shows it is not possible to detect the effect of CNB modulation of the shift of the mirrors under current technology.

But we could alway use other approach like the one proposed by L. Stodolsky. 4

16.2.1.6. Neutrino Capture on Unstable Nuclei¶

This is from the paper by Vogel. 1

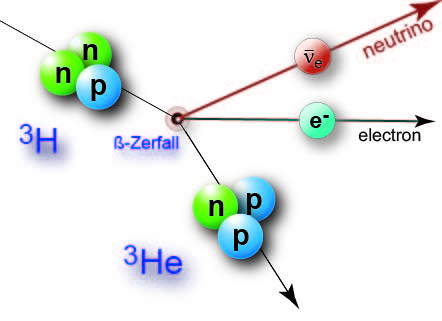

A nulei \(A_Z\) that captures a electron neutrino will become \(A_{Z+1}\),

Since a nutron is transformed into a proton through \(\nu_e + n\to e^- + p^+\), releasing energy \(Q\) which is called the \(Q\) value,

By definition, \(Q\) is the sumation of the kinetic energy difference of electrons and neutrinos,

since we have the conservation of energy

The beta decay \(Q\) value of \(A_Z \to A_{Z+1} + e^- + \bar \nu_e\) is given by

The kinetic energy of electrons is

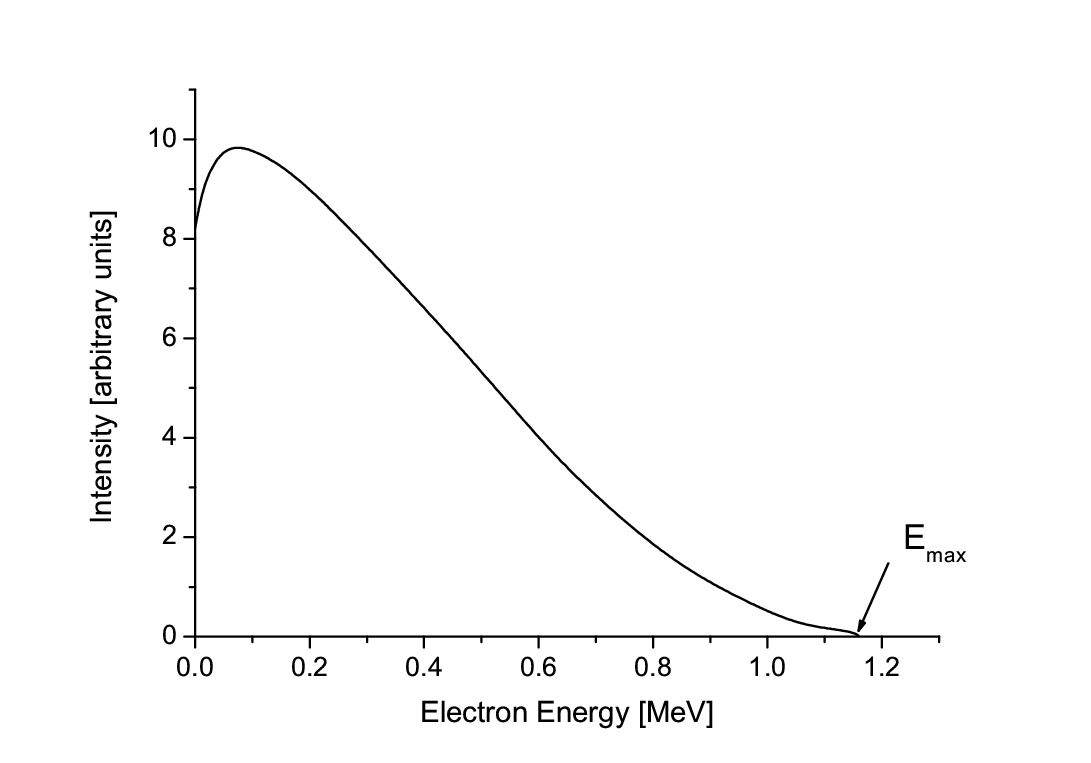

Fig. 16.4 Beta dacay spectrum. From File:Beta spectrum of RaE.jpg@Wikipedia¶

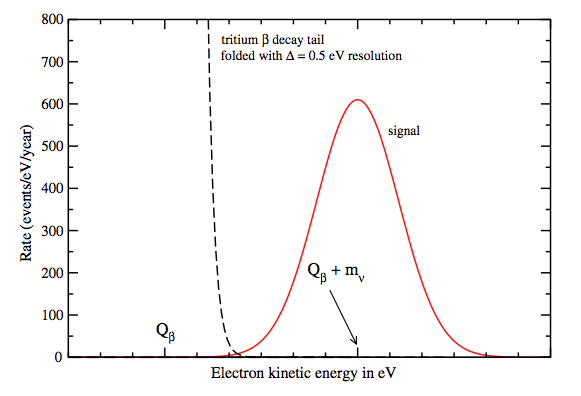

The key point comes next. In beta decay, the maximum electron kinetic energy is given by \(Q_\beta\), which means that even in a beta decay beckground, the electrons that is responsible for the neutrino capture is still distinguishable because their energy is larger than the the beta decay electrons’ energy. The difference is as large as \(2 m_{\nu_e} + K_{\nu_e}\) or \(2 m_{\nu_e}\) as we are talking about CNB neutrino with \(K_{\nu_e}\to 0\).

Even though it sounds feasible at this level, here are several questions to ask.

What nuclei should we use?

How many of such nuclei is needed? Can we produce them? Is is feasible to build a detector with so many such nuclei?

The first question is related to cross section and life time. Large cross section and a suitable life time of the unstable nuclei \(A_Z\) are needed. We also need to make sure that the signal we want can be seperated from the background beta decay signal.

Anyway, what do we choose to use as the detector? Tritium.

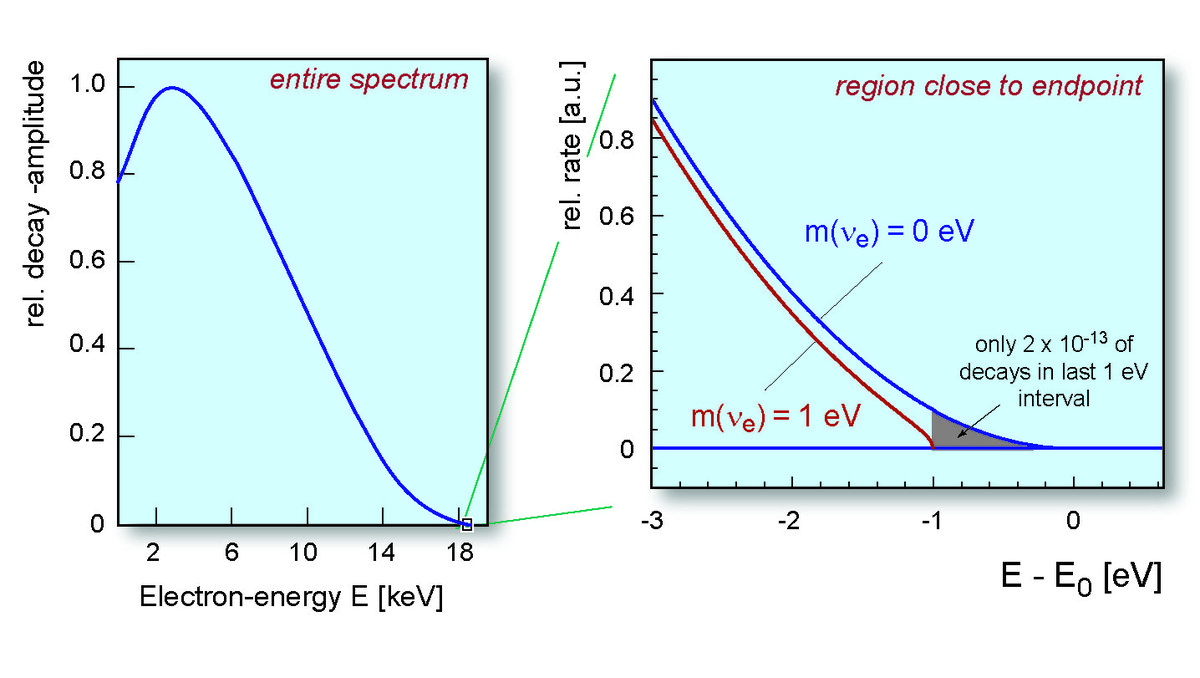

Fig. 16.5 Tritum decay spectrum. From KATRIN.¶

Tritum decay has a very clean and small tail. Since it is relatively light, the decay is more sensitive to neutrino mass. The life time is 12.3 years which is not too long nor too short.

We can estimate the material needed for such a detector using cross section of beta decay. The meaning of cross section is almost the reaction rate divided by the initial flux, in more accurate language,

Reaction rate means number of reactions per unit time, which is what we need to calculate the required mass of detector. The reaction rate of capture on tritium is calculated using 1

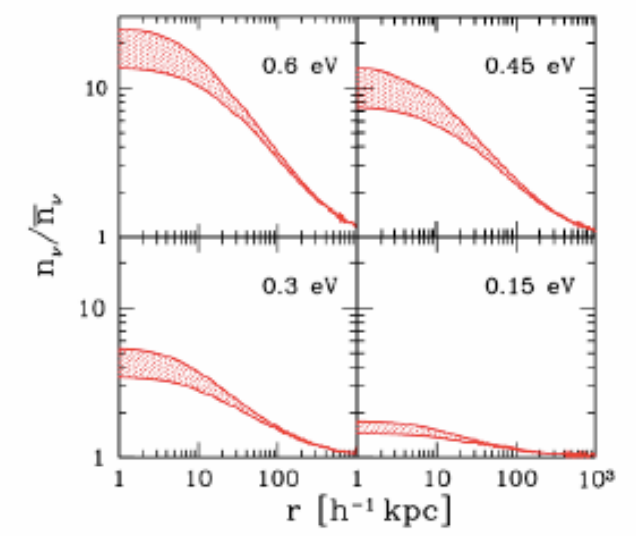

where \(\frac{n_\nu}{\langle n_\nu \rangle}\) accounts for the fact that the number density of CNB neutrinos at the detector (Earth) might be larger than the average in the whole universe due to gravity of our galaxy or some other effects. We also used the cross section of neutrino capture on tritium \(\sigma=1.5\times 10^{-41}\frac{m_\nu}{1\mathrm{eV}} \mathrm{cm}^2\).

Fig. 16.6 Local enhencement of neutrino number density. From Formaggio’s talk at int¶

We estimate the reactions for tritium \(\mathrm{{}^3H}\) mass \(m_t\) during time \(t\),

For tritium, the result is that \(100\mathrm{g}\) will result in about 83 events per year if we use \(n_\nu/\langle n_\nu \rangle =10\).

So we need a detector of tritium mass of the order 100 gram or more.

The problems, though, are also significant.

Separate the CNB neutrino capture from the beta decay background requires a hell good of precision in energy detection. If the energy resolution is not enough to resolve a \(2m_\nu\) energy difference, then the signal is hardly seperable.

Tritium molecules capture a neutrino and become a \(t He^3\) which has rotational and vibrational energy about \(0.36\mathrm{eV}\). This will cause a restriction on the energy resolution.

Emitted electrons can be scattered by the tritium thus causing a energy redistribution.

Other Background

Solar neutrino of pp reaction is not a issue because the energy range 0eV to 10eV only has a neutrino number density \(10^6\mathrm{cm}^{-2} \mathrm{s}^{-1}\). This is less than 1 percent of the effective flux of CNB. 9

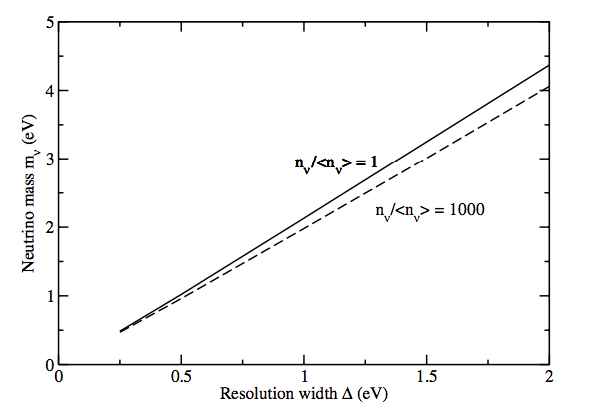

As for the resolution problem, we can estimate the requirement. 8

To calculate number the events in a energy interval, we only need to integrate the rate over the F-D distribution. The ratio of the events from captured CNB neutrino and events of beta decay is

where \(\Delta\) is the width of the resolution. The actual result is 1

A more precise numerical calculation assuming mass of neutrino \(m_\nu=1\mathrm{eV}\) and resolution \(\Delta = 0.5\mathrm{eV}\) shows that we need at least a resolution that satisfies \(m_\nu/\Delta > 2\) where \(n_\nu/\langle n_\nu \rangle = 50\) is used. 9

Fig. 16.7 Seperation of signals for \(n_\nu/\langle n_\nu \rangle = 50\). From R. Lazauskas, P. Vogel and C. Volpe, J. Phys. G 35, 025001 (2008).¶

Fig. 16.8 For the signal strength \(N_\nu/N_\beta\) to be 1, the relation of mass and resolution. From R. Lazauskas, P. Vogel and C. Volpe, J. Phys. G 35, 025001 (2008).¶

16.2.2. Refs & Notes¶

- 1(1,2,3,4,5,6,7)

Vogel, P. (2015). How difficult it would be to detect cosmic neutrino background? (Vol. 025001, p. 140003). doi:10.1063/1.4915587 .

- 2

Cabibbo and L. Maiani, The vanishing of order-G mechanical effects of cosmic massive neutrinos on bulk matter Phys.Lett. B114, 115 (1982).

- 3

Langacker, J. P. Leveille and J. Sheiman, On the detection of cosmological neutrinos by coherent scattering Phys. Rev. D 27, 1228 (1983)

- 4(1,2)

Stodolsky, Speculations on Detection of the “Neutrino Sea” Phys. Rev. Lett. 34, 110 (1975); (erratum) Phys. Rev. Lett. 34, 508 (1975).

- 5(1,2)

Lewis, R. R. (1980). Coherent detector for low-energy neutrinos. Physical Review D, 21(3), 663–668. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.21.663.

- 6(1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8)

Weiler, T. (1982). Resonant Absorption of Cosmic-Ray Neutrinos by the Relic-Neutrino Background. Physical Review Letters, 49(3), 234–237. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.49.234

- 7

- 8

Cocco, G. Magnano and M. Mesina, JCAP 0706, 015 (2007). 22.

- 9(1,2)

Lazauskas, P. Vogel and C. Volpe, J. Phys. G 35, 025001 (2008).